Pollination

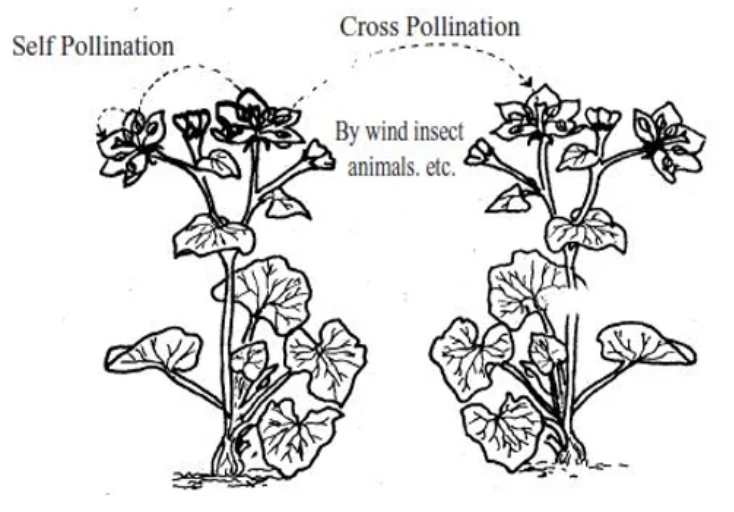

Pollination is the process by which mature pollen grains are transferred from the anthers to the mature stigmas of flowers. There are two main types of pollination:

- Self-pollination

- Cross-pollination

Cross-Pollination

Cross-pollination occurs when pollen grains from one flower are transferred to the stigma of another flower on a different plant of the same species. This method is often risky and inefficient, as many pollen grains fail to reach the target stigma. However, cross-pollination promotes genetic diversity among offspring, which tends to make them healthier and better adapted to their environments.

Characteristics of Cross-Pollination

- Male and female reproductive parts are located in separate flowers.

- In dioecious plants, male and female flowers occur on different plants of the same species.

- In monoecious plants, where male and female flowers

are

on the same plant, self-pollination is prevented

through

mechanisms such as:

- Stamens maturing before the stigmas (protandry).

- Stigmas maturing before the stamens (protogyny).

- Some flowers exhibit self-sterility, where pollen from the same plant cannot fertilize its own ovary due to slow or no pollen growth on the stigma. Examples include leguminous plants and Ixora.

- In some upright flowers, the stamens are positioned below the stigmas to ensure insects touch the stigmas before the stamens, preventing self-pollination.

Self-Pollination

Self-pollination occurs when pollen from the anther is transferred to the stigma of the same flower or another flower on the same plant. This process is common in short-lived annual plants and has a high success rate. However, it results in offspring with little genetic variation.

Characteristics of Self-Pollination

- In composite plants like sunflowers, cross-pollination is initially attempted (protandry). If it fails, self-pollination occurs when the stigmas curl back to collect the remaining pollen.

- Some flowers do not open, ensuring self-pollination (e.g., cleistogamous flowers).

- Certain flower structures, like those of caladium (ornamental cocoyam), trap insects to facilitate self-pollination.

Insect and Wind Pollination

Flowers are typically pollinated by insects or wind. The structural adaptations of flowers are influenced by the type of pollination they use.

Agents of Pollination

- Wind (Anemophily): Pollen grains are lightweight and adapted for dispersal by air currents. Wind-pollinated plants produce large quantities of small, light pollen grains. Examples include grasses, pine, oak, wheat, and corn.

- Water (Hydrophily): In aquatic plants, pollen grains are released into water and carried to stigmas. This method is rare and typically seen in submerged or floating plants.

- Insects (Entomophily): Bright colors, patterns, and scents attract insects like bees, butterflies, and beetles. These insects transfer pollen as they feed on nectar.

- Other Animals: Birds like hummingbirds and sunbirds, as well as some mammals, also aid in pollination. They are often attracted by specific flower traits such as bright colors or unique structures.

Insect-Pollinated Flowers

- Have brightly colored parts to attract insects.

- Produce rough pollen grains that stick easily to insects.

- Emit a strong fragrance to lure pollinators.

- Feature broad or sticky stigmas to ensure efficient pollen transfer.

- Produce nectar, a sugary liquid that serves as food for pollinators.

- Contain stamens located inside the flower.

Wind-Pollinated Flowers

- Are often unisexual.

- Produce abundant pollen grains.

- Have light, smooth pollen grains that easily float in the air.

- Feature large, branched, and leathery stigmas to capture airborne pollen.

- Lack nectar and scent.