Atomic Structure

Thomson Model

Thomson proposed an atomic model that visualized the atom as a uniform sphere of positive charge with embedded negatively charged electrons. He also determined the charge-to-mass ratio (e/m) of electrons and found that this ratio remained constant for all cathode ray particles, regardless of the gas in the tube or the metal used.

Rutherford Model

Rutherford introduced a planetary atomic model, suggesting that the atom consists of a dense, positively charged core called the nucleus, where most of the atom's mass is concentrated. Surrounding this nucleus, negatively charged electrons orbit much like planets around the sun. To maintain electrical neutrality, the number of electrons must equal the number of protons in the nucleus.

Limitations of the Rutherford Model

- It predicted that atoms should emit light over a continuous range of frequencies, whereas experimental results showed discrete line spectra.

- It suggested that atoms should be unstable, with electrons spiraling into the nucleus. However, atoms are generally stable in reality.

- The model failed to explain experimental observations, leading to modifications introduced by Niels Bohr.

Bohr's Model

Bohr proposed a refined model of the hydrogen atom with the following key ideas:

Postulates of Bohr’s Model

- Electrons move around the nucleus in specific circular orbits called energy levels. The centrifugal force from this motion balances the electrostatic attraction between the electron and the nucleus. Electrons can move in these orbits without losing energy, and only certain discrete orbits are possible.

- The energy of an electron is quantized, meaning it can only take specific discrete values. Electrons do not lose energy continuously but make energy transitions in quantum jumps, emitting or absorbing energy in the form of photons.

- The frequency of emitted light during an electron

transition is given by:

$$ hf = E_u - E_l $$

Where:- Eu = Energy of the upper state

- El = Energy of the lower state

- h = Planck’s constant (6.67 × 10-34 Js)

- f = Frequency of emitted light

- Electrons absorb energy when moving to higher energy levels (excitation).

- Electrons emit energy as photons when moving to lower energy levels.

- The angular momentum of an electron in an atom is

also quantized, given by:

$$ L = n\frac{h}{2π} $$

Where n is a quantum number (1,2,3...).

Successes of Bohr’s Model

- It explained why atoms emit line spectra and accurately predicted the wavelengths of hydrogen's spectral lines.

- It provided an explanation for absorption spectra, where photons of specific wavelengths excite electrons to higher energy levels.

- It explained atomic stability by stating that the ground state is the lowest energy state for an electron, preventing further energy loss.

- It correctly predicted the ionization energy of hydrogen as 13.6 eV.

Electron Cloud Model

This model describes the atom as having a small, dense nucleus with a radius of about 10-10 to 10-15 m. Instead of revolving in fixed orbits, electrons move rapidly within a large region around the nucleus, spending most of their time in areas of high probability, forming an electron cloud.

Unlike earlier models that depicted electrons as small particles in fixed orbits, this model considers electrons as wave-like entities with probabilistic distributions around the nucleus. The electron cloud is denser in regions of higher probability and more diffuse in areas of lower probability.

Atomic Structure and Chemical Behavior

Modern atomic theory describes the atom as having a dense, massive nucleus at the center, surrounded by a cloud of electrons that move in wave-like orbits.

Subatomic Particles

- Protons: Positively charged particles found in the nucleus. Each proton has a charge of +1.6 × 10-19 C and a mass of 1.67 × 10-27 kg.

- Neutrons: Neutral particles found in the nucleus, with a mass similar to protons.

- Electrons: Negatively charged particles with a charge of -1.6 × 10-19 C and a much smaller mass of 9.1 × 10-31 kg.

Atomic Number and Mass Number

An atom is represented as AZX, where:

- Z (Atomic Number): The number of protons in the nucleus.

- A (Mass Number): The total number of protons and neutrons.

Isotopes

Isotopes are atoms of the same element with the same atomic number (Z) but different mass numbers (A). This means they have the same number of protons but different numbers of neutrons. Because chemical reactions involve the exchange of valence electrons, isotopes exhibit similar chemical properties.

Energy Levels in an Atom

Electrons in an atom are arranged around the nucleus in specific positions known as energy levels or electron shells. Removing an electron from the first energy level requires more energy compared to removing electrons from higher levels.

Electron Energy Equation

The energy of an electron is given by:

\[ E = -\frac{R}{n^2} \]

Where:

- \( E \) = Energy of the electron

- \( n \) = Electron quantum number

- \( R \) = A constant

The negative sign indicates that work must be done to remove the electron from the atom.

Ground State and Excited State

The ground state of an atom is its most stable state, corresponding to its minimum energy. When an atom is heated or absorbs energy from an external source, it enters an excited state, where its energy is higher and the atom becomes unstable.

Electron Volt (eV)

One electron volt (\(1eV\)) is the energy gained by an electron when it moves freely through a potential difference of 1 volt:

\[ 1eV = 1.6 \times 10^{-19} \text{ J} \]

Energy Conversion and Electron Motion

During excitation from a lower energy level, the potential energy is converted into kinetic energy, allowing the electron to move with velocity \( v \) according to the equation:

\[ K.E = \frac{1}{2} m v^2 = eV \]

where:

- \( m \) = Mass of the electron

- \( v \) = Velocity of the electron

- \( e \) = Charge of the electron

- \( V \) = Potential difference

Energy Transition Between Levels

Electrons in an atom occupy definite energy levels with specific values such as E₀, E₁, E₂, E₃, etc. An electron can transition between energy levels. For example, an electron can absorb energy and move from the lowest energy level (ground state E₀) to a higher level En, or it can lose energy and transition from E₃ to a lower level E₂.

When an electron moves between energy levels, the energy difference is given by:

\[ E_n - E_0 = hf = \frac{eV}{\lambda} \]

where:

- \( E_n \) = Energy of the higher level (n = 1, 2, 3...)

- \( E_0 \) = Energy of the lower level/ground state

- \( h \) = Planck’s constant=

- \( f \) = Frequency of emitted or absorbed radiation

- \( \lambda \) = Wavelength of emitted radiation

The greater the energy change, the higher the frequency of the emitted radiation.

According to the quantum theory proposed by Max Planck, heat or electromagnetic radiation is emitted in fixed, discrete amounts known as quanta. The energy E of a photon or quantum is given by:

$$ E = hf $$

Where:

- h = Planck’s constant = 6.6 × 10-34 Js

- c = Speed of electromagnetic waves in free space = 3.0 × 108 m/s

- λ = Wavelength of the electromagnetic wave (m)

- f = Frequency of the electromagnetic wave (Hz)

Example

An electron transitions from an energy level Ek to the ground state E₀. If the frequency of emission is 8.0 × 1014 Hz, what is the energy emitted?

Given:

- h = 6.6 × 10-34 Js

- f = 8.0 × 1014 Hz

Solution:

Using the formula:

E = hf

E = (6.6 × 10-34) × (8.0 × 1014)

E = 5.28 × 10-19 J

Thus, the correct answer is 5.28 × 10-19 J.

Spectra of Light

A gas emits light only when energy is supplied to its atoms. When a gas atom absorbs energy, it becomes excited. This excitation can occur through heating or by passing an electrical discharge through the gas, typically achieved by applying a high voltage across a tube containing the gas at low pressure. The light emitted consists of multiple spectral lines.

Definition of Spectrum

A spectrum is an arrangement of entities in order of increasing or decreasing magnitude.

Types of Spectra

1. Emission Spectra

Emission spectra refer to the light emitted directly from a source, such as a hot gas. They are categorized into three types:

(i) Line Spectra

Line spectra consist of distinct and separate bright lines of definite wavelengths. They are produced by gases or vapors at low pressure, such as:

- Sodium in a sodium vapor lamp

- Mercury in a mercury vapor lamp

- Gases in discharge tubes

(ii) Band Spectra

Band spectra appear as groups of closely spaced lines that fade at one end. These spectra arise from the excitation of molecules in glowing gases or vapors, often seen in:

- Calcium or barium salts in a Bunsen flame

- Discharge tubes containing molecular gases

(iii) Continuous Spectra

Continuous spectra are produced by solids and liquids or by gases at high pressure. An example is the filament of an electric lamp.

2. Absorption Spectra

Absorption spectra are formed when a material absorbs part of the radiation emitted by a source. The resulting spectrum, observed using a spectrometer, is called an absorption spectrum. It is categorized into three types:

(i) Line Absorption Spectrum

This occurs when white light passes through a monoatomic cold gas and is analyzed with a spectrometer. The spectrum exhibits dark lines corresponding to bright lines in the emission spectrum.

(ii) Band Absorption Spectrum

When white light passes through a gas composed of multiple atoms (e.g., iodine vapor or a dilute solution of blood), dark bands appear against a bright background.

(iii) Continuous Absorption Spectrum

These spectra occur when white light interacts with solids or liquids. For example, when white light falls on a green plate, the material absorbs all colors except green, producing a continuous absorption spectrum.

Wave-Particle Paradox

Light is a form of electromagnetic radiation that exhibits wave-like properties such as reflection, refraction, and interference. However, certain phenomena, like the photoelectric effect and the Compton effect, cannot be explained solely by the wave theory.

To explain the photoelectric effect, Albert Einstein proposed that light travels as discrete packets of energy called photons. These photons interact with electrons, causing emission.

Thus, light behaves as a wave in interference and diffraction experiments but as a particle in phenomena like the photoelectric and Compton effects. This dual nature of light is known as wave-particle duality. Other electromagnetic waves exhibit similar behavior.

De Broglie Hypothesis

In 1923, the French physicist Louis de Broglie proposed the wave-particle duality theory, which states that a moving particle has an associated wavelength given by:

\[ \lambda = \frac{h}{p} \]where:

- \( \lambda \) = wavelength of the associated wave

- \( h \) = Planck's constant

- \( p \) = momentum of the particle

Examples of Wave-Particle Duality

Phenomena where waves exhibit particle-like behavior:

- Photoelectric effect

- Compton effect

Phenomena where particles exhibit wave-like behavior:

- Electron diffraction (used in electron microscopes)

- Neutron diffraction

Thermionic Emission

Metals contain many free electrons that move randomly at high speeds between atoms. When these electrons gain enough energy, they can escape from the metal surface. This process is similar to fish swimming in a pond. The fish move around and occasionally leap out of the water, creating a dynamic balance where as many fish leave as return.

If the fish gain more energy, they leap out more frequently and reach higher before falling back. If an incentive, like a worm, is provided, the fish will leave the pond in a continuous flow. Similarly, when a metal is heated, its free electrons gain enough energy to escape.

What is Thermionic Emission?

Thermionic emission is the release of free electrons from a heated metal surface. It occurs when the metal reaches a very high temperature, supplying the electrons with enough external energy to break free.

Applications of Thermionic Emission

Thermionic emission is essential in many electronic and communication devices, including:

- Vacuum tubes

- Diode valves

- Cathode ray tubes

- Electron tubes

- Electron microscopes

- X-ray tubes

- Radios

- Thermionic converters

- Electrodynamic tethers

Photoelectric Effect

The photoelectric effect occurs when light shines on a metal surface, causing electrons to be ejected. This phenomenon provided key evidence that light is quantized, meaning it is carried in discrete packets.

Key Laws of the Photoelectric Effect

- Electrons are emitted only if the light's frequency is above a certain threshold.

- If the frequency is high enough, increasing the light's intensity increases the number of emitted electrons.

- The maximum kinetic energy of emitted electrons depends on the frequency of the light, not its intensity.

Albert Einstein explained the effect by suggesting that light consists of discrete particles (photons) with energy proportional to their frequency:

$$E = hf$$

where \( h \) is Planck's constant.

This idea was originally proposed by Max Planck to explain blackbody radiation.

Applications of the Photoelectric Effect

- Used in photocells, commonly found in solar panels, to generate electricity.

- Photoelectric cells are used in burglar alarms.

- Used in photomultiplier tubes to convert light intensity into electrical currents.

- Applied in X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS).

- Used in scintillators, which emit light when exposed to radiation from cosmic or lab sources.

- Used in digital cameras to detect and record light.

- Used in motion and position sensors.

- Found in applications such as photostatic copying, photodiodes, light meters, and phototransistors.

- Used in light sensors, such as those in smartphones, for automatic screen brightness adjustment.

Photoelectric Equation

The energy of an incident photon is given by:

\[ E = W_0 + E_k \]

Where:

- \( E \) = Energy of the photon

- \( W_0 \) = Work function of the metal

- \( E_k \) = Maximum kinetic energy of the emitted photoelectrons

From Einstein’s photoelectric equation:

\[ hf = h f_0 + \frac{1}{2} m v^2 \]

Rearranging for the photoelectric equation:

\[ hf = W_0 + eV \]

The maximum energy \( (E) \) of the emitted electrons is given by:

$$E = hf_o - W$$

Threshold Wavelength and Frequency

The work function \( W_0 \) is related to the threshold frequency \( f_0 \) by:

\[ W_0 = h f_0 \]

Using the relation between frequency and wavelength:

\[ f_0 = \frac{c}{\lambda_0} \]

Substituting in the work function equation:

\[ W_0 = \frac{h c}{\lambda_0} \]

Kinetic Energy of Emitted Electrons

The maximum kinetic energy of emitted electrons is given by:

\[ \frac{1}{2} m v^2 = eV \]

Where:

- \( \lambda_0 \) = Threshold wavelength (m)

- \( f_0 \) = Threshold frequency (Hz)

- \( V \) = Applied stopping potential

- \( m \) = Mass of the electron

- \( v \) = Velocity of the emitted electron

Stopping Potential

The stopping potential in photoelectric emission is given by:

\[ eV_s = E_k \]

From Einstein’s photoelectric equation:

\[ eV_s = h f - W_0 \]

Rearranging for the stopping potential \( V_s \):

\[ V_s = \frac{h f - W_0}{e} \]

Where:

- \( V_s \) = stopping potential (V)

- \( e \) = elementary charge (\( 1.6 \times 10^{-19} C \))

- \( E_k \) = maximum kinetic energy of photoelectrons (J)

- \( W_0 \) = work function of the metal (J)

Example

The maximum kinetic energy of the emitted photoelectrons from a metal surface is given as \( 0.34 eV \). If the work function of the metal is \( 1.83 eV \), find the stopping potential.

Solution:

Given:

\[ E_k = 0.34 eV, \quad W_0 = 1.83 eV \]

Using the equation:

\[ h f = W_0 + E_k \]

\[ h f = 1.83 + 0.34 = 2.17 eV \]

Now, solving for stopping potential:

\[ V_s = \frac{E_k}{e} = \frac{0.34 eV}{e} \]

\[ V_s = 0.3417 V \]

Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle

The Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle states that it is impossible to measure two canonical variables (such as momentum and position) simultaneously with high precision.

Canonical Variables

- Momentum and position

- Energy and time

Mathematical Expressions

The uncertainty relations are given by:

\[ \Delta x \cdot \Delta p \geq h \] \[ \Delta E \cdot \Delta t \geq h \] \[ \Delta x \cdot \Delta v \geq h \]Explanation of Variables

- \( \Delta x \) = Uncertainty in position measurement

- \( \Delta p \) = Uncertainty in momentum measurement

- \( \Delta t \) = Uncertainty in time measurement

- \( \Delta v \) = Uncertainty in velocity measurement

X-Ray

X-rays are a form of electromagnetic radiation with very high frequencies. They were discovered by the German physicist W. Roentgen in 1895.

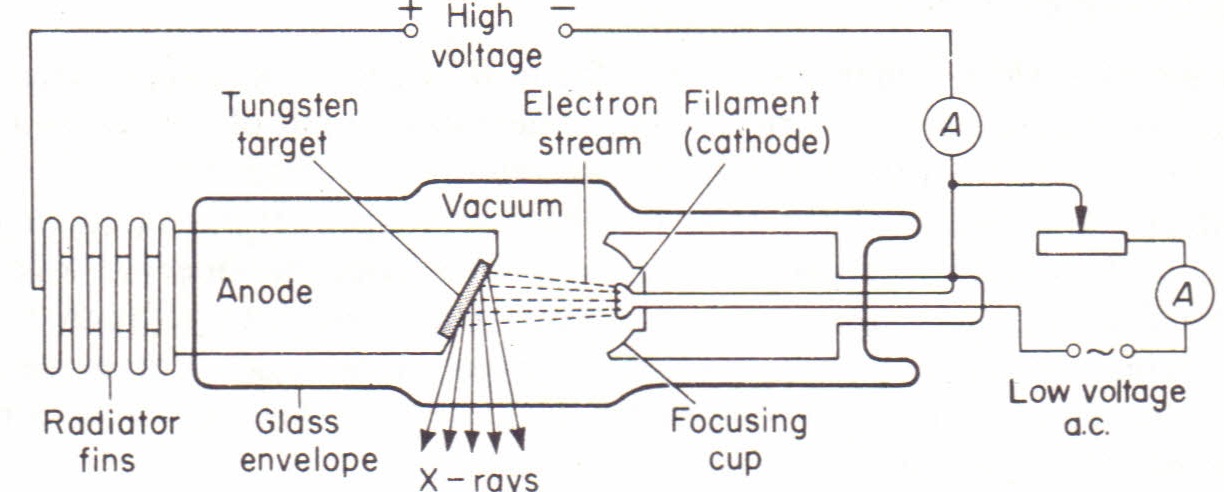

X-rays are produced when high-speed electrons are suddenly stopped by a target material. During this process, a portion of the kinetic energy of the electrons is converted into X-rays, while the remaining energy is dissipated as heat. Typically, only about 1% of the energy is transformed into X-rays, while the other 98% is lost as heat in the anode. X-ray production is essentially the reverse of the photoelectric effect.

Credit: PhysicsMax

Credit: PhysicsMax

Production of X-Rays

X-rays are generated in a Coolidge tube, which operates as follows:

- The cathode is heated, causing it to emit electrons via thermionic emission.

- A high voltage between the anode and cathode accelerates these emitted electrons.

- The accelerated electrons collide with a target material at the anode, producing X-rays.

The energy of an accelerating electron is given by:

\[ E = eV \]

The maximum energy of the X-ray produced is equal to the energy of the electron:

\[ hf_{\max} = eV \]

where:

- \( E \) = Energy of the electron

- \( e \) = Electronic charge

- \( V \) = Accelerating potential

- \( h \) = Planck’s constant

- \( f_{\max} \) = Maximum frequency of emitted X-ray

Components of a Coolidge Tube

The Coolidge tube consists of the following main parts:

- Thermionic Cathode: Emits electrons when heated.

- Anode: A copper block with a target material that stops the electrons and produces X-rays.

- High Voltage Source: Provides a large potential difference (~50,000V) to accelerate electrons toward the anode.

- Cooling Fins: Dissipate heat from the anode to prevent overheating.

The characteristics of the X-rays produced depend on the target material and the potential difference between the anode and cathode.

Properties of X-Rays

- They have very short wavelengths (~\(10^{-11}\) to \(10^{-8}\) m).

- They travel in straight lines.

- They exhibit wave properties such as reflection, refraction, and diffraction.

- They affect photographic plates.

- They can penetrate most materials.

- They travel at the speed of light (~\(3.0 \times 10^8\) m/s).

- They can be blocked by lead.

- They ionize Gases

- Unaffected by both magnetic and electric fields

Types of X-Rays

1. Hard X-Rays

- Have higher frequencies.

- Possess shorter wavelengths.

- Are more penetrating than soft X-rays.

- Produced by high tube voltage.

2. Soft X-Rays

- Have lower frequencies.

- Possess longer wavelengths than hard X-rays.

- Are less penetrating.

- Produced by lower tube voltage.

Uses of X-Rays

- Medical imaging and diagnostics.

- Treatment of cancerous cells (radiotherapy).

- Industrial analysis and quality control.

- Security screening at airports.

- Agricultural applications for pest and disease control.

- Authenticity verification of artwork.

Compton Scattering

Compton discovered that when X-rays strike matter, some of the radiation is scattered. Additionally, some of the scattered radiation has a longer wavelength than the incident radiation. The change in wavelength depends on the angle at which the radiation is scattered.

Compton Scattering Equation:

\(\lambda_1 - \lambda = \frac{h}{m_e c} (1 - \cos \phi)\)

Where:

- \(\lambda\) = Wavelength of incident radiation

- \(\lambda_1\) = Wavelength of scattered radiation

- \(h\) = Planck's constant

- \(m_e\) = Mass of an electron

- \(c\) = Speed of light

- \(\phi) = Angle through which the radiation is scattered

Compton scattering cannot be explained using classical electromagnetic theory, which predicts that the scattered wave should have the same wavelength as the incident wave. However, experimental observations show a shift in wavelength, supporting the quantum nature of light.

Differences Between X-ray Spectra and Optical Spectra

X-ray Spectra

- X-ray spectra from different metals have a similar appearance.

- Each spectrum represents energy changes close to the nucleus.

Optical Spectra

- Optical spectra vary for different metals.

- Each spectrum represents energy changes in the outermost electron shells.

Hazards of X-rays

- Exposure to X-ray to lead to Cancer

- X-rays could burn the skin

- Exposure to X-rays can destroy the body's cell and tissues

- Exposure to X-ray leads to mutations in the DNA

Precautions against X-rays include limiting the number of X-rays, wearing protective gear such as lead coats and using the lowest possible exposure settings.